The Preferred Road for PEI Agriculture

![]()

In early 2004, I was contracted by the PEI National Farmers Union to research and write a brief for submission to the PEI government. It offered a comprehensive, up-to-date critical assessment of the state of farming, food and the environment in PEI at the time (Part I) and then went on to map out a preferred road for agriculture (Part II); a new path that would take us beyond the monocultural, chemical-based, corporate model of agriculture doing so much damage to farm families, rural communities, the land, water, air. The practical programs, plans and projects proposed needed emerge from these principles, values and vision – they are still feasible and even more urgent today. I sincerely hope this analysis and policy suggestions are given serious consideration by those holding the reigns of political power and responsible for agricultural policy in PEI.

+ + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + +

The Preferred Road for PEI Agriculture

A brief submitted to the Standing Committee on

Agriculture, Forestry and Environment

National Farmers Union

District 1, Region 1

February 25, 2004

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

1. Introduction

For more than three decades, the National Farmers Union has been calling attention to political policies and practices which impact negatively on food producers and consumers. Since it’s beginning in 1969, the NFU has also been trying to organize farmers and consumers to work together for an alternative to an unjust and damaging food system. The National Farmers Union continues to call for fundamentally new and different measures, to enable both producers and consumers to regain control of their own production and consumption of food. There is too much wealth being generated by the food system for consumers to be paying such high prices for food. Especially when farmers often don’t receive the cost of production.

There have been some successes over the years, however large corporations have continued to grow larger. The best successes have been marketing approaches like supply management or price sharing at the Canadian Wheat Board. These marketing systems work to get farmers a higher share of the value of their produce because they are spared from having to compete with one another. We must debunk the myth that farmers need to become more ‘competitive’. The truth is that farmers receive more money by not competing with one another, against the conventional wisdom which says that out-competing fellow producers by producing cheaper and selling cheaper must continue to define the rules of the agricultural marketing system.

The existence of a global agri-business economy dominated by huge corporations demanding cheap raw farm commodities has been strengthened greatly in recent years. The statistics in this brief will show just how much. Because of the consolidation of ownership and control in the hands of fewer global corporations in the food business, this situation will undoubtedly guarantee low prices to farmers for the foreseeable future within the present structures.

Governments have been unwilling to force agri-business to share a greater portion of the wealth that comes from the food which farmers produce. It seems our federal government believes that farmers are not supposed to get a fair share of the food dollar. Consider what the former federal Minister of Agriculture, Hon. Lyle Vanclief, said to Western Producer reporter Barry Wilson when asked about the persistent low returns to farmers: “The reality is that for the most part, people who produce resources are price takers, not price setters. That’s the way it is.” [Western Producer, June 1, 2001]. Why can’t farmers set and receive a fair price for their products? When the answer becomes, ‘because that’s the way the system works,’ then it’s obviously time to change the system.

In recent years, agribusiness corporations have consolidated their power on a global basis. They have profited and increased their capacity to influence political decision-making everywhere, especially in international bodies like NAFTA and the World Trade Organization (WTO). As a result, they have been able to shape the future direction of agriculture for PEI, Canada and the entire world.

Yet, present-day agricultural policies and practices are unable to prevent a range of negative environmental problems affecting all of us, producers and consumers. In fact, they are causing most of them. Solving negative environmental problems related to farming will only happen if attempted solutions are designed to address the systemic source of those problems. Implementing ‘stop-gap’ measures will not prevent the continued demise of family farming.

Marketing and organization go hand and hand. The NFU holds that if farmers market individually they will continue to have no power to set prices in an unregulated global marketplace dominated by large agri-business corporations. New forms of ‘orderly marketing’ organizations are needed to pool producer and consumer power in the marketplace. The only way for Islanders to gain greater power to set a higher price under current marketing structures and policies is through new forms of producer & consumer marketing organizations based on voluntary membership and clear rules. The NFU believes it is in everyone’s best interest for PEI to move swiftly in this direction, and it is therefore clearly the role of PEI government to see that such processes are initiated and encouraged. The window of opportunity to act may be short; now is clearly the time to embark on a new road for agriculture.

With a few exceptions, government agricultural policies support industrial agriculture and thereby help to contribute to the loss of family farms and the further dissolution of rural Island communities. Government policies on the one hand, and the absence of creative new initiatives on the other, make our government doubly complicit in the acceleration of a number of such negative agricultural trends. This presentation examines these political and economic policies which are not economically viable for farm families.

The NFU is convinced that it is only when consumers and family farmers organize and work together for change that solutions to problems within Island agriculture and our food system will be found. The PEI government must provide the initiative and resources to enable all Islanders to chart a different course for agriculture and the food system.

Government incentives and services formerly offered to farmers under the terms of the 15-year comprehensive development plan gave support to Island farmers to change their farm operations into larger, more mechanized farms. Food production methods became dependent on large doses of chemicals and artificial inputs. That comprehensive plan launched in 1969 has transformed farming and the food system on PEI. We need a new plan that gives farmers control of the production and marketing of the food they produce; a plan that will accelerate a transition to sustainable farming practices which rely on natural inputs and sustainable farming methods.

The road ahead for PEI agriculture must begin with the government taking steps to first stabilize and strengthen farmers in their current situation, and then begin to implement new production and marketing measures which will see farmers receive a greater share of the consumer food dollar.

The NFU calls on the PEI government to formulate a new comprehensive plan for PEI. The NFU is confident that farmers will embrace and give their full support to a new comprehensive long-term agricultural strategy. Farmers have already shown tremendous cooperation and support for measures that require them to change or adopt new farming practices to become more sustainable. They are willing to comply with environmentally conscious laws such as buffer zones and crop rotation restrictions. However, farmers must be assured that they can make a decent living growing healthy food in a way that does not damage the environment.

The full cooperation of all Islanders, consumers and farmers, is needed to realize the objectives of the agricultural strategy suggested in this brief. Such a plan must address the needs of all farmers who are now struggling to produce healthy food, protect the environment and make a decent living. They will not be able to do this without support from both the Canadian and PEI governments.

To know what things need to be supported and undertaken, it is first necessary to understand the core problems within our food system. This brief therefore begins with an examination of some key facts about today’s agricultural food system. We first look at the national and international agricultural system within which Island farmers and consumers must participate and survive. We then examine negative impacts on PEI resulting from the trends. We conclude with suggested elements of a preferred road for PEI agriculture and the food system.

2. Part I: Agriculture and the Food System on PEI

Core problems in Island agriculture are clearly systemic in nature. Recent statistics, facts and circumstances indicate that the farm crisis is not accidental. It is based on decisions and actions which have predictable outcomes. Those problems result from agricultural policies and farm practices which force farmers to produce food for an illusive profit they never seem to attain. These problems can not only be identified and discussed separately, we can also see that they are intrinsically related. They have a common source in the dominant economic system which defines farming and food production today.

2.1 The Unsustainable Nature of Industrialized Food Production

A particular model for food production drives agriculture on P.E.I., and throughout the world, commonly referred to as Industrial Agriculture. This model of farming is based on certain attitudes, laws, policies and practices which work together to create an economic food system. They create an elaborate network of ‘needs’ on the farm which are addressed with the purchase of corporate inputs.

Within Industrial Agriculture, the production of food is regarded as a business like any other. To remain a viable business, farmers are told that they must be competitive in an unregulated, global marketplace. The primary objective is to increase production and profits.

The economic theory which farmers follow to realize increased profits is often referred to as the ‘economy of scale’ approach. This theory holds that ‘bigger’ is more efficient and cost-effective when combined with commodity ‘specialization’. However, production efficiencies derived from economies of scale do not compensate farmers for below-the-cost-of-production commodity prices. For example, despite the fact that P.E.I. witnessed a consistent increase in the number of acres of potatoes grown during the 90’s, the total farm value of potatoes did not increase at the same rate as production. In 1986 there were 64,219 acres of potatoes planted with a total farm value of $103,728,000. Ten years later there were 110,000 acres of potatoes planted (45,781 acres more than in 1986) with a total farm value of just $138,956,000. [Source: Potato Historical Series 22-008-XPB, Potato Production Bulletin, 22-008-UPB]. And we are all aware of the disastrous situation facing potato farmers this year – news that a Russian company will give farmers approximately half the cost of production (3 cents a pound) is billed as ‘good news’, and are warehouses full of potatoes that can not even be given away for free.

Industrial agriculture is an approach to food production which actually destroys living organic processes and natural productive processes in the soil, over time, through the systematic extraction of nutrients and organic material. The soil eventually becomes depleted, incapable of producing food without large amounts of chemical fertilizers, insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides. To bring the soil back to health requires sustainable practices and natural inputs.

The industrial approach to farming causes many serious environmental and social problems for P.E.I. It is, however, well suited to recent trends to liberalize trade in food. Large-scale industrial production of single commodities brings food surpluses within given regions, and the need to export that food to other countries. Industrialized nations have introduced export-oriented food policies which have decreased local food security in countries throughout the world. They also allow corporations to profit, expand and increase control of the food system.

2.2 Corporate Concentration & the Global Liberalization of Food Trade

The deepening crisis in Canadian and Island agriculture has its source in the fundamental principles and laws entrenched in international Free Trade Agreements which work to bring about predictable negative outcomes for farmers and consumers. We need to understand how these principles and laws work to benefit multinational agri-business corporations if we are to understand where this system will eventually, and inevitably take us if fundamental changes based on different principles and laws are not soon brought into force.

Corporate concentration has been happening at a steadily increasing pace for years. Mary Hendrickson and William Heffernan, with the Department of Rural Sociology at the University of Missouri, offer the following data on concentration in the United States: the biggest four companies own 81% of beef packers, 59% of pork packers, 46% of pork production, 50% of broilers, 45% of turkeys, 25% of animal feed plants, 60% of terminal grain handling facilities, 81% of corn exports, 65% of soybean exports, 61% of flour milling, and 80% of soybean crushing. [1] A more recent study indicates that three agribusiness firms now control 82% of corn exports. [2]

Corporate concentration has occurred at every level of the economic food system. In 2001,Wal-Mart became the #1 food seller in the United States. Wal-Mart has not yet begun to sell food on PEI, however this is likely to happen in the not-too-distant future. If they do, this is what consumers will be up against: Walmart is the biggest retailer in the world, with sales larger than the gross domestic product of Ireland and Israel combined. [3]

According to sociologist Darell McLaughlin, Free Trade does two things simultaneously: (a) it erases economic borders between nations and forces the world’s one billion farmers to compete with one another in an unregulated market; and (b) it encourages the biggest and most powerful corporations to become even bigger and more powerful through acquisitions, takeovers and mergers.

As a result, large, mostly foreign-based corporations have significantly increased ownership and control of Canada’s food system. Have trade agreements, increased foreign ownership, increased food exports and corporate concentration been good for farmers and consumers? Research undertaken by the National Farmers Union offers the following comparison of several key economic indicators after fourteen (14) years of free trade. [4]

Considered together, the information shows just how devastating the impact of trade liberalization has been for Canadian farmers and for our national and provincial food security. Although agri-food exports increased by $17.3 billion, realized net farm income increased by only .2%. This indicates that all the new wealth generated from increased food exports has been taken by corporations involved in the food system, including large food processors, food shippers, brokers and traders, and food retailers, along with corporations that sell farm chemicals, fertilizers, pharmaceutical products and farm machinery.

During the first seven (7) years of NAFTA, Archer Daniels Midland’s profits went from $110 million to $301 million, while Cargill’s net earnings from 1998 to 2002 jumped from $468 million to $827 million. Both Corporations figure within the ‘top four’ in most of categories mentioned earlier. [5]

The present situation points to an entrenched and unfair distribution of wealth within the food system, with family farmers and consumers paying the price. The NFU believes that new trade laws and rules for agriculture work against producers and consumers, and work to benefit agri-business. In the era of free trade, creative new approaches to re-establish farmer and consumer control of our food system must be taken at the provincial level to mitigate against the negative impacts of the increasing corporate control of food.

2.3 The Effects of Industrialized Agriculture on Prince Edward Island

With the release of recent agricultural statistics from the 2001 Census, it becomes easier than ever to see that things are definitely worsening in the area of family farming, food security, and loss of control over our food system. The statistics support our experience at the grocery store. The extent of the corporate control of food was recently evident as Islanders watched news reports of beef farmers selling cattle for pennies (if they could sell them at all) while being asked to pay dollars per pound at the major food retailers. The full significance of agricultural trends and farm figures can only be realized when a range of key factors are considered together.

2.3.1 The Continuous Decline in the Number of PEI farms

One of the most significant trends affecting PEI is the loss of family farms. We are witnessing the near elimination of the rural farm population. Approximately 70 years ago, nearly the entire rural population of P.E.I. was made up of farmers and their families. In 1996 it was 7%. Today, only 5.8% of the total population of PEI live on farms. There has been a steady and accelerating decline in family farms on PEI:

As can been seen from the information in the following chart, during the 5 year period between 1996 and 2001, the number of PEI farm operators declined by 16.2% overall, but smaller farms are disappearing at the most alarming rate. The number of remaining farms with acreage in each PEI county are as follows:

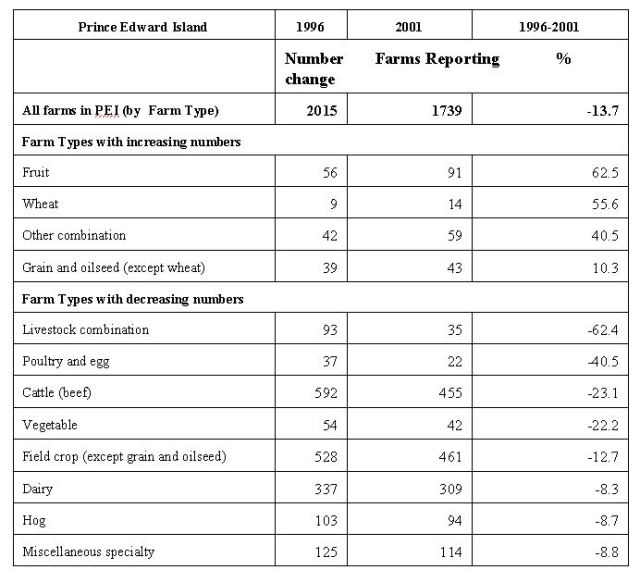

The rate of farm loss in the last five (5) year census period by commodity can be seen in the following chart which gives farms reporting in the 2001 census with gross farm receipts of $2,500 or more by farm type:The following chart gives the percentage of farms in each county based on commodities:

The number of remaining farms, with acreage, in each PEI county is as follows:

The rate of farm loss in the last five (5) year census period by commodity can be seen in the following chart which gives farms reporting in the 2001 census with gross farm receipts of $2,500 or more by farm type:

The following Chart gives the percentage of farms in each county based on commodities:

2.3.2 The Continuously Increasing Size of Farms

The loss of farms has been directly linked to another trend, the increasing number of large farms specializing in one farm commodity. The following chart shows the steady increase in the number of large farms over the past two decades:

Compounding the problem is a complementary trend where the number of smaller-acreage farms is rapidly decreasing:

The highest number of farmers who left farming were smaller farmers: 59% of farmers making less than $100,000 left farming; 42.5% of farmers with farm capital between $100,000 and $200,000 left farming in the five (5) year period from 1996-2001.

2.3.3 The Deepening Farm Financial Crisis

The primary reason for the decreasing number of farms on P.E.I. has been the farm financial crisis; the primary cause of the farm financial crisis has been the persistent inability of farmers to receive a fair return for their products in the marketplace. A secondary cause can be traced to insufficient farm income adjustment and stabilization programs.

Net cash income – the difference between a farmer’s cash receipts and operating expenses – tumbled 10.6% in Canada in 2002 ([Source: Statistics Canada). Realized net farm income is calculated before any allowance is made for the value of farm labor or management. Nor does this income figure take into account principal payments on farmland. This means that farmers are even losing money farming when the figures show a profit. Along with a persistent problem in achieving adequate income, farmers are plagued with debt. The most recent Census data shows that debt is increasing at an accelerated rate. There was nearly a three-fold increase in the 10 year period from 1991 to 2001. [6]

2.3.4 The Rising Cost of Retail Food and Decreasing Farmer Share

Although Canadian consumers spend a lower portion of their disposable income on food than do consumers in other industrialized countries in the world [7], prices have still continued to rise at the same time as the farmer’s share of that rising cost has decreased.

The Centre for Rural Studies and Enrichment at St. Peter’s College [8]offers the following price comparisons to illustrate the increasing inequity in the food system:

A similar trend is evident in other countries. According to a World watch Report released in September, 2000 titled “Agribusiness Concentration Not Low Prices is Behind Global Farm Crisis,” we read:

As globalization accelerates, the food industry is becoming more vertically integrated, with many of the more profitable functions once performed by farmers now being taken over by giant agricultural conglomerates such as ConAgra and Novartis….In the United States, the share of the consumer’s food dollar actually going to the farmer has declined from more than 40 cents before 1950 to about 7 cents today.

The gap between farm gate and retail food prices in Canada increased in the 80s at about four times the rate that it did in the United States.[9]

The report makes it clear that there is a direct correlation between low returns to farmers and the disappearance of farmers. It suggests that in Poland, 1.8 million farms could disappear in the next few years. In Sweden, half of the farms are expected to go out of business in the coming decade, and in the Philippines, half a million farms in the Mindinao region alone are expected to go out of business. All because of corporate concentration and the inability of farmers to receive a cost of production return from the sale of their products.

Agriculture Canada food bureau economists indicated in a 1999 report that agri-business corporate concentration is expected to continue. We do not have to rely on statistics from experts to see that agri-business is steadily displacing farmers in favour of corporate-owned food production.

We have also witnessed this consolidation of retail food sales happen in our communities. In 1996, supermarket/grocery stores controlled 83% of retail food sales. They control an even greater degree today. And the processing sector has also witnessed a trend of stable returns on investments. In their study, “An Analysis of Profits within the Canadian Food Processing Sector,” Rick Burroughs and Deborah Harper rely on Statistics Canada data to examine profitability trends in the Canadian food processing industry compared to other manufacturing industries during the period 1990-1998. Ninety-six (96) food processing enterprises per year were studied. The study gave the following result: “Rate of Return for the food processing industry ranged from a high of 13.1% in 1990 to a low of 10.4% in 1997, with an average of 11.6% over the nine-year period” [10]. The study also concluded that “large enterprises [defined as enterprises with sales of $100 million or more] are more profitable than medium and small enterprises in the food processing sector, with an average rate of return for the nine year period of 12.6% annually. Again, there are fewer and larger food processing corporations gaining a greater share of the market value of food. Some of that profit is no doubt a result of efficiencies because of size. There is also an ‘economy of control’ working with the economy of scale that

explains the real truth behind corporate profits, growth and increasing control of food.

John M. Connor, professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University, discusses the emergence of global cartels in recent years in his book: “The Globalization of Corporate Crime: Food and Agricultural Cartels of the 1990’s. He reports that between 1988 and 1992, more than 20 global cartels were formed by manufacturers from Europe, Asia and North America, mostly food/feed ingredients industries. Although Anti-Trust laws exist in most industrialized countries, including Canada, they have not been able to prevent price-fixing conspiracies by global cartels. Connors tells us that since 1997 approximately 85% of all fines for price-fixing have been imposed on food and agriculture cartels with ‘affected commerce’ (sales by members of a price-fixing conspiracy) of just those instances that were discovered since 1996, estimated at $76 billion [11].

2.3.5 The Continued Degradation and Erosion of PEI’s Land

P.E.I.’s system of farming is having serious and long-term negative impacts on the quality of farmland and the fertility of Island soils. The causes stem from monoculture farming and include: compaction from heavy equipment; fall ploughing of larger fields with fewer hedgerows; and the destruction of organic material, earthworms, nitrogen-fixing bacteria, etc. from the heavy use of chemical fertilizers.

In the Report of the Action Committee on Agricultural Runoff Control [Agriculture & Forestry Technology and Environment, October, 1999] the systemic source of this problem is clarified:

Prince Edward Island’s geography, geology, and land use, which have resulted in low organic matter levels, have combined to create the potential for serious environmental problems. The soils are highly erodible, and with some 263 watersheds throughout the Island, the impact of soil erosion on surface water quality and marine habitats is significant….Soil erosion is the single most important environmental problem in the Province, resulting not only in unacceptable levels of soil loss and degradation, but also in unacceptable levels of surface water contamination, siltation and marine habitat destruction….The nature of the Island’s agriculture industry has increased the potential for soil erosion. The recent expansion in potato acreage has intensified the risk. Between 1989 and 1995, total production increased from 68,000 to 108,000 acres and has increased marginally to 113,000 acres by 1999….Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada estimates that more than 80 percent of cultivated land in the province is at high-to-severe risk of water erosion. (p.2-3)

Addressing the problem of soil degradation and erosion means changing the practices which are causing those problems. Too many potatoes are being grown; too many mixed farms are disappearing. A government-support transition strategy to increase diversification is urgently needed. Given the present degree of damage, a new political action plan is required to bring about the rehabilitation and restoration of depleted land. It is not enough that the PEI government set targets for increasing organic matter in the soil. The government must work with farmers to undergo a major shift in farming methods and practices that will see chemical inputs gradually replaced with natural inputs and sustainable farm practices.

2.3.6 The Contamination of Land and Water from Farm Chemicals

Farm chemicals are a major problem in Island agriculture. The rate of use of farm poisons (herbicides, insecticides, fungicides) increased rapidly during the 90’s. In 1993, Island farmers used a total of 602,000 kilograms of these three types of poison (measured in kilograms of active ingredient); by 1996, that amount had increased to 1,053,900 kilograms [PEI Department of Agriculture – Review of 1996 Spray Season].

The PEI government has recently established the objective of “…reducing pesticide use, and in particular the application of high toxicity products by 25% by 2003 and 50% by 2011, as compared to the baseline year (2000).” [12] Such an objective is good, but can not be achieved without negatively impacting farmers unless support measures and transitional funding are made available to farmers.

Along with herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides, the heavy use of fertilizers is producing rising levels of nitrates causing problems in Island waters. We can appreciate the seriousness of this situation when we consider that Islanders are 100% dependent on groundwater for our freshwater supply. It is imperative that we move quickly to replace chemical fertilizer with natural, organic nutrients.

The total amount of chemical fertilizer and limestone applied to Prince Edward Island soils has more than doubled from 1990 to 1998 [41,192 tonnes in 1990; 84,255 tonnes in 1998. Source:The Atlantic Fertilizer Institute]. [13]Although some efforts are being made to reduce chemical fertilizer use, we have a long way to go before achieving significant decreases. Statistics Canada data reveals that 1232 farms on PEI reported using commercial fertilizer on 272,069 acres of farmland in 2002.

The PEI government recently indicated that: “…average nitrate levels in private wells have increased steadily since 1984-85; and in 2002, 5.2% of wells exceeded the 10 mg/l guideline in the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality.” [14] The percentage of wells exceeding the safe limit continues to rise: in 2000 it was 3.5%; in 2001, 4.9%; in 2002, 5.2%.

3. Part II: A Preferred Road for PEI Agriculture

The vision of Agriculture the NFU holds out for the future of P.E.I. has little in common with the picture of farming and agricultural evident today. Policies and programs must be designed and implemented to arrest the demise of family farming and the dissolution of rural communities. Such policies must encourage a process to rehabilitate the farm sector, repair and prevent environmental damage, and establish farming that relies on truly sustainable production practices.

A preferred road ahead is clear: our government must put new marketing structures and regulations in place to ensure farmers receive a greater return for their products. Without higher prices, investments in sustainable farming will be impossible. Some would argue that with the rapid increase in global corporate ownership and control of the food system, measures to bring increased prices are doomed to fail. Yet, there is mounting evidence that investing in sustainable agriculture and local economic capacity can contribute to rural community revitalization. [15]

3.1 The Public Will for Change

Farm, rural and food issues only seem to become issues in political election campaigns on PEI when extraordinary circumstances exist, like drought, potato wart, or the BSE crisis. The deepening crisis in farming and the food system has not been on the political agenda in recent provincial elections. Nor was Canadian agriculture an issue in the last Federal election. The farm population apparently comprises too small a percentage of the general population to represent a significant vote margin for candidates on the campaign trail. Public attitudes and beliefs are clearly changing on PEI, however, and food and farming are now becoming important political issues.

Islanders have become increasingly aware of problems related to industrial farming, mostly as a result of environmental damage from the use of farm chemicals, or from erosion. They also see exorbitant costs at the grocery store while farm families are forced out of farming because they are earning too little. Many more Islanders are now also aware of the increasing threats to health and safety posed by the use of farm chemicals.

PEI government research on public opinion on pesticides indicates this changing attitude among Islanders. Of particular interest is the shift in public opinion regarding the belief that pesticides are necessary for modern agriculture on PEI: in the three years from 2000 to 2003, 10% fewer islanders believe that pesticides are necessary to modern agriculture:

Many positive and important first steps have already been taken by farmers, farm organizations, and the provincial government in the past few years. It is also fair to say that most Islanders now have enough understanding of the negative impacts of chemical-based industrial agriculture to support a new direction. Islanders know that the land can not simply be used for maximum production and profit. It represents our main resource for food security, and must be respected as an intricate complex of natural life processes and sustainable, balanced ecosystems. Political policies and programs must be based on the basic beliefs and principles that flow from this fundamental attitude of respect for the land and the environment.

3.2 Agricultural Policy Framework Agreement: A Political Mechanism for Change

The NFU holds that a political plan for a preferred agricultural system on PEI must entail comprehensive agricultural and food policy for PEI. If it is to succeed, the PEI government must consult extensively with farmers and the public. It must then negotiate with the federal government to get assistance with the implementation of this plan through the Federal-Provincial Agricultural Policy Framework (APF) and Implementation agreements.

PEI has recently signed on to the APF, and has more recently negotiated an Implementation Agreement. This new APF agreement between PEI and the federal government is the first such comprehensive agreement on agriculture and food since the 1969 Comprehensive Development Plan.

In a news release [16] on September 12, 2003, Minister of Agriculture, Hon. Lyle VanClief, indicated that the APF would be renegotiated annually: “I am announcing today an annual review of all elements of the new Agricultural Policy Framework (APF). This will provide producers with additional comfort that any challenges arising from the new programs in the APF will be addressed.” The agreement states that it will recognize “…the need for flexibility in how these goals would be reached and respecting jurisdictions and responsibilities.” As it stands, the APF is clearly geared to further the global aspirations of food corporations, since the agreement states that it’s purpose is to “set out an integrated and comprehensive policy framework to enhance the profitability of the agriculture and agri-food sector…” The challenge for the PEI government is to develop its own policy framework to enhance the profitability of agriculture through a change away from industrialized to sustainable agriculture.

The actual agreement leaves considerable room for the PEI government to map out its own vision and strategy for agriculture and food, then negotiate with the federal government through the APF for support. There are already many aspects of the framework agreement that could support a new long-term plan for agriculture and food on PEI. The basis of that plan must include the basic beliefs and principles discussed in the following section.

Until new mechanisms and organized ways to recoup more from the sale of PEI’s food are implemented, farmers will need to rely on government support programs. The current terms of those federal-provincial agreements are contained in Section A: Business Risk Management section of the APF, and the implementation agreement. Risk Management Programs, like the Net Income Stabilization Account (NISA), are based on previous-year averages. When realized net farm income is so low for so many years in a row, the average does not ‘stabilize’ farm income, it ensures that farmers have another year without realized net income. A provincial government interim financial agreement would seek a new formula under the APF that offers farmers cost-of-production and a margin of profit.

3.3 Principles and Goals of an Agricultural Strategy for PEI

PEI needs a government with vision and leadership willing to broaden agricultural policy decision making beyond mere economics. It must look at the big, long-term picture and recognize that a basic public trust is at stake: our rural way of life and control over our food and environment. A democratic society like PEI can still create a food system which is based on sustainable principles, social justice, and the common good. A system of global agribusiness and food production practices which farmers are dependent upon is not a preferred road for agriculture for PEI’s future.

If we are to respect the natural production of food; bring about the necessary conditions to produce healthy food; and allow our increased awareness of the negative impacts of the industrial economic system of agriculture on people and the environment to guide our decision-making, then we need to first adopt a different set of principles than those of industrial agriculture. Principles, beliefs and goals such as:

- Family farms are the backbone of Island agriculture. Initiatives in a new agricultural strategy must be financially viable, strengthening the economic well-being of farmers. The full cost for such initiatives can not be borne by farmers alone.

- Policies must be designed to protect farmers from an unregulated and unfair global market.

- Agricultural policy must be designed to ensure farming is a rewarding, relatively stress-free and viable lifestyle. This is the only way to guarantee food security for consumers and security of livelihood for farmers.

- Food is essential to life. Food must not be regarded simply as a commodity for commercial trade in the same way as computers or cars. Ensuring continuous access to an adequate amount of healthy food is the most basic responsibility for the PEI government. This belief must constitute the cornerstone of a future agricultural strategy.

- Food production is a natural – not a synthetic – process involving many interdependent aspects of interconnected ecosystems. These ecosystems involve many living beings, are delicate, and are comprised of natural resources which are not inexhaustible.

- A future PEI Agricultural policy will understand that domestic food requirements must take priority over export trade in agricultural commodities. Strategies to increase export trade should not be linked to product specialization, i.e., more and more potatoes for french fries, but should be based on the promotion of agricultural biodiversity in keeping with a practical strategy to achieve sustainable agriculture.

- The government must implement programs and provide tangible support to farmers to allow them to accelerate a transition to sustainable farming. Significant compensation must be given when farmers take land out of farming to protect the environment, or reduce intensive farming with increased crop rotation. The cost of a transition to farming with fewer and fewer chemical inputs must be borne by everyone.

- A comprehensive agricultural strategy must be based on the belief that consumers have a right to healthy food which is produced in a way that does not negatively impact the health of people or the environment. Consumers have a right to know what they are eating, as well as how the food they purchase is produced. People also have a right to know if genetically-altered food is being sold to them, or if it is being produced on PEI.

- P.E.I. needs more farmers, not fewer farmers. We need more smaller mixed-farms and fewer large farms. If this is ever to happen, it will be necessary to implement marketing mechanisms that ensure that farmers receive a better than cost-of-production return for their produce. Measures must be implemented to ensure that farm income is sufficient to provide a reasonable and fair standard of living.

Based on beliefs and principles such as those above, it becomes clear that the primary objective of a comprehensive strategy is to promote food production methods and techniques which are essential to healthy food production and environmental sustainability [17 ] at the same time as offering support to farmers to remain farming, and begin to implement measures to reduce costly chemical inputs. The primary goal of all agricultural policy will therefore be to assist in the transformation of the food production system on P.E.I. into a sustainable agriculture with a gradually increasing number of farmers moving to natural rather than artificial and chemical inputs. Based on such principles, a comprehensive agricultural and food policy must do the following:

- take into account the wider social, cultural and environmental connections in the development of agricultural policy;

- seek to establish co-operation and co-ordination among relevant governmental agencies and between the different stakeholders, farmers organizations, farm families, food processors, and consumers;

- use a balanced mix of policy instruments such as legislation & regulations; the development of an effective and publicly-accountable marketing council with the appropriate marketing infrastructure; various financial instruments such as grants and low-interest loans; and education and extension services to farmers, and research and development;

- establish environmental quality criteria and goals for all program initiatives

- ensure that implemented policies are cost-effective on the farm level;

- provide incentives to farmers to assist in the transition to sustainable agriculture;

- explore the use of economic instruments as a means to transfer external environmental costs (currently regarded as the sole responsibility of farmers) to the public realm, in recognition of the public benefits derived from healthy food production practices, and the social significance of keeping farmers farming.

The transformation of agriculture in PEI would happen in conjunction with a Safe Food policy. Key aspects of a Safe Food policy affecting farm practice would include the following:

- Genetically-engineered foods will not be permitted to be grown on PEI. They have not been proven safe. They can not co-exist with organic crops without eventually contaminating those crops through cross-pollination, thereby rendering them ‘non-certifiable’ as organic.

- Antibiotics would only be administered to animals to treat disease;

- Growth hormones will be disallowed;

- Monitoring and regulatory measures will be put into place to ensure compliance with aspects of a Safe Food Code of Practice;

- A grading system for meat plants would be implemented.

- A PEI Label that can guarantee the above conditions would quickly win premium prices from buyers in domestic and international marketplace.

3.4 Policies and Programs for a Future PEI Food Strategy

To achieve the transformation of agriculture the government of PEI must design and implement a series of policies and programs. These will need to be administered separately, however they must also be part of an interrelated plan which aims to achieve a transformation of the entire agriculture and food system in PEI. Once the elements of this plan are developed, they will also need to be relied on to negotiate a new agreement with the federal government under the terms of the Agricultural Policy Framework agreement.

Particular policies and programs should support change in the direction of achieving three interrelated objectives:

- To ensure financial security to farmers by stabilizing and increasing net farm income;

- To increase the number of farms in PEI;

- To promote increased chemical-free farming through sustainable farming.

3.4.1 Programs to ensure financial stability for PEI farmers

Policies and Programs are urgently needed to support farmers suffering financial losses as a result of problems for which they are not responsible. Programs must be put in place to provide farmers adequate financial support to farmers. An approach to developing a comprehensive agricultural and food policy for PEI must begin by ensuring that adequate interim financial support is available to farmers to remain farming. It is only in this way that we will be able to stem the further loss of family farms and the further concentration of primary food production. It is clear that greater efforts must be made to establish more control of marketing farm produce. This is the only way farmers can get a greater share of the value of the food they produce. Financial support programs must be improved until a Farm Marketing Council is established and able to garner a cost of production return to farmers for their products.

3.4.2 Establishing a PEI Farm Marketing Council

One of the first and most important steps needed to chart a new course for PEI Agriculture is to negotiate federal financial supports under the terms of the APF to do marketing work directly on behalf of farmers. To facilitate this initiative, the NFU is calling on the PEI government to establish a Provincial Farm Marketing Council with the two-fold mandate of (1) encouraging the organization of farmers to market collectively and price share, and (2) developing and securing markets for PEI producers. Looking to the future, there is no other way farmers will be able to receive a fair price for their products. This council would not limit itself to market development and product promotion, but would serve as a catalyst in assisting Island farmers to organize price-pooling for a range of farm commodities. There are a number of key marketing initiatives the PEI government could, and should, launch.

Countries throughout the world, especially Europe, have populations of people opposed to genetically-modified foods. These markets for GMO-free and chemical-free farm produce could bring great wealth to PEI. A forward-thinking transitional strategy would see the provincial government negotiate long-term contracts with food brokers and processors in Europe, Asia and other regions of the world, then contract farmers to produce produce for those international markets. The revenue from such sales would pay for the per acreage payouts to farmers needed to undergo a transition away from chemical farming. The PEI government could begin to establish such direct-from-farmer international marketing through trade missions and joint federal-provincial initiatives such as the most recent one announced in August for corporate food export companies. Minister Lyle Van Clief announced on August 14, 2003 nearly $600,000 for Atlantic Canada Food Companies to “…get the edge they need to carve out new export markets with the help of $578,4233 in federal funding.” [18] The money is earmarked for food companies to “…help companies assess new markets, make contacts and keep current on export issues such as shipping logistics, labeling legislation and border clearance requirements.” VanClief notes that “Projects expected to flow from this funding are exactly the types of international market development activities we are trying to encourage through the Agricultural Policy Framework (APF).” As noted earlier, food processors are already reaping a very healthy annual profit margin; it is farmers who need this marketing assistance, not processors.

3.4.3 Implementing a Transition to Sustainable Food Production

A transition program is foundational, and must inspire all other programs of the department of Agriculture, Forestry and Environment. The objective of this program would be achieved following a two-fold strategy (1) to facilitate and encourage existing farmers to begin a transition away from chemical-based farming to chemical-free farming; and (2) to encourage new farmers to begin farming without the need for toxic chemicals.

If sustainable farming is to flourish, it will need sustained support from a range of government policies. Following the lead of other jurisdictions such as Denmark and Sweden [19], financial support programs would need to be put in place to assist farmers in the transition to sustainable, chemical-free farming. To help farmers over the transitional period when yields can drop temporarily, a mortgage guarantee or an interest free loans must be made available to farmers who adopt a farm plan to convert from chemical-based, monoculture farming to sustainable farming.

The inadequate number of people – especially young people – who are deciding to begin farming – coupled with an aging farm population – threatens the future viability of farming on P.E.I. A program offering technical and financial incentives to new farmers is needed. The New Farmer Program we have now is nowhere near sufficient to address the true costs of beginning farming. A new farmer program must be tied to the objectives of the transition strategy and would offer an opportunity to promote smaller, mixed-farming operations based on organic and sustainable farm practices. Compliance with sustainable farming practices would be required to receive grants or other incentives through the program.

3.4.4 Increasing Agricultural Extension Services and Supports to Farmers

One of the most important inputs for sustainable farming is knowledge. Many farmers believe they have no choice but to use toxic chemicals to control pests. A greatly expanded budget and role for government extension services would provide farmers with knowledge about such things as how soil enrichment produces healthy plants that resist disease, how certain cover crops can retard erosion and control weeds, and how natural predators help to control pests. Applying this knowledge will allow farmers to reduce and eventually eliminate their use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, saving them money and protecting the environment.

Farmers are dependant on adequate education and training to be able to practice production methods that will lead to sustainable agriculture. As the knowledge on sustainable agriculture will increase over time, due to research and practical experience, it will be a necessary ongoing program for government to keep farmers up-to-date with the latest developments.

3.4.5 Research in Sustainable and Organic Agriculture

Agricultural research requires that the government implement a series of targeted

publicly-funded research programs. These research initiatives will aim…

- to develop research programs to increase sustainable agriculture on P.E.I.;

- to utilize the wisdom already developed on sustainable farms on P.E.I., and to enlist and adequately remunerate farmers in developing new research project;

- to promote strategic and applied research that will assist farmers to determine what must be done either to convert to chemical-free farming, or to begin farming organically. Such services would include the development of sustainable technology and integrated chemical-free farm plans geared to individual farms;

- to promote practical knowledge concerning the environmental, social and economic aspects of sustainable agriculture and the benefits of organic farming

- to develop cost-effective and simpler methods of monitoring the quality of surface water and groundwater;

- to develop and implement methods of monitoring the soil (nutrient and organic matter losses, heavy metals, toxic chemicals, nuclides);

- to co-ordinate research endeavors with other organizations and jurisdictions promoting sustainable agriculture;

- to implement on-farm demonstration projects for sustainable farm practices. Projects would include topics such as: proper handling and use of manure, slurry and urine; demonstrations of new agricultural machinery suited to sustainable farming; integrated pest management; on-farm composting; soil tillage; biodiversity and crop rotation experimental trials to demonstrate re-circulation of nutrients and organic matter from bio-waste;

- to engage in on-farm natural plant breeding and the conservation of old species.

3.4.6 Public and School-based Education on Sustainable Farming

To ensure that the benefits of sustainable agriculture are understood and supported in the long-term, public education is essential. Important aspects for education and training will be:

- to make sure that all levels (farms, agricultural schools, extension service, universities & research institutes) are included in the education program and are reached by the same information and knowledge;

- to oversee the development of courses for different education levels on sustainable development in agriculture;

- to promote public awareness of the benefits of sustainable and organic farming to ensure the environmental, cultural, social and economic values and functions of agriculture are understood and supported;

- to encourage the use of information technology for the promotion of sustainable farming objectives.

3.4.7 The establishment of an Agricultural Land Banking System

Those who want to begin farming are often prevented from doing so due to the price of land. The price of agricultural land is clearly prohibitive. A Land Banking System would offer long-term affordable leases to farmers. It would be tied to adoption of a sustainable farm plan.

3.4.8 Implementing an Agricultural Land Policy

There is currently no zoning policy on P.E.I. to protect land for farming. The implementation of such a policy is essential to protect P.E.I.’s farmland for the future. Besides ‘zoning’ agricultural land, an agricultural land policy would legislate a number of farm practices directly related to the use of land.

3.4.9 Prohibiting the production of Genetically-Modified Crops

Growing genetically-engineered crops is incompatible with the objective of promoting natural food production. It threatens organic certification status, lucrative world markets, and is unnecessary. It must be prohibited. Farmers need to be supported in practicing production methods which do not threaten human or animal health or degrade the environment, including bio-diversity and integrated pest management. Non-renewable resources must be replaced gradually by renewable resources and the re-circulation of non-renewable resources. Sustainable agriculture and organic farming must be vigorously promoted to create stable well-developed and secure rural communities on P.E.I.

3.4.10 Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling of Food & Purchasing Local Farm Produce

Consumers have the right to chose to buy ‘local’ produce rather than imported food. The provincial governments must encourage a strategy whereby retail food outlets in PEI are challenged to buy more local produce and make it known to consumers that local produce is available, and have mandatory country of origin labeling on food. In addition, all provincial government facilities, including hospitals and public schools, should buy local farm produce whenever possible.

Conclusion

Farming must be regarded as a partnership between human beings and the ecosystem in which we live. It is a common concern for us all. It sustains all living things. It must be treated with understanding and respect. And it should be controlled by the people, not the dictates of agri-business bolstered by an economic system based on the narrow goal of making profits by extracting resources and wealth. Islanders need leadership to organize and increase both producer and consumer power in the marketplace.

There is an urgent need to speed up a transition of the agricultural sector on P.E.I. With consumers demanding foods that have been produced naturally without the use of chemicals or genetic-engineering, P.E.I. must dedicate itself to a transition from monocultural, industrial farming to diversified, sustainable agriculture.

The production of food using natural farm practices and inputs is a realistic strategy for P.E.I. Our Island comprises 1.4 million acres, 646,000 of which are cleared for farming. Our cooler climate and the fact that we are an Island makes us ideally positioned to dedicate ourselves to such a transitional strategy. We could become a model show case for progressive, creative changes needed in many other jurisdictions. The ‘smallness’ of the Island, the interconnectedness of people, and the easy access to policy makers are all significant advantages for a long-term strategy aimed at transforming agriculture into a truly ‘sustainable’ agricultural system.

There are initial costs to be borne, however, those costs represent a tremendous investment in the future health and well-being of all Islanders. Other countries are providing support to farmers to encourage practices that make food healthier with fewer or no chemical inputs. This change in direction is the only sensible option given the present system of agriculture which is flawed and untenable. The production of safe food through farm practices that do not poison or damage the environment is the only sane path for PEI to take.

PEI is often referred to as the ‘garden of the gulf’. Making our garden fertile and keeping it healthy requires that we base our food production on natural farming practices which enhance the fertility and health of the soil, protect the purity of our water, and respect and encourage the co-existence of many different species of plants and animals.

Decisive and clear political leadership is required to make this happen. With a concerted effort and a high degree of public support for a transformation of Island agriculture, achieving the vision and goals suggested in this brief will be possible.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

ENDNOTES

1. Mary Hendrickson and William Heffernan, Department of Rural Sociology at the University of Missouri, February, 2002.

2. Missouri Rural Crisis Centre news release, http://www.commondreams.org/news2003/0711-03.htm.

3. Margot Ford McMillen, Rural Routes:Top 10 Food Issues, [www.populist.com/02.2.mcmillen.html].

4. A complete copy of this report can be downloaded from the NFU website at http://www.nfu.ca.

5. See, “The Global Free Trade of Food: Trading Away Family Farms and Consumer Choice,” at http://www.farmaid.org/event/info/facts_global.asp. See also, Factsheet on U.S. Agriculture and trade policy, national Family Farm Coalition, 2003.

6. Farm Debt Outstanding: Agricultural Economic Statistics, Statistics Canada Agricultural Division, Farm Income and Prices Section, Catalogue No. 21-014-XIE, Vol. 1, No.2, (ISSN: 1705-0901), November, 2002.

7. According to 1999 figures, Canadian consumers paid 9.8% of their disposable income on food, Americans paid 10.9%; Australia paid 14.6%; and Japan paid 17.8%. Barry Wilson, Western Producer Special Report, June 1, 2000.

8. Diane J. F. Martz and Wendy Moellenbeck, “The Family Farm in Question: Compare the Share Revisited,”Centre for Rural Studies and Enrichment, St. Peter’s College, Muenster, Saskatchewan, January, 2000. Found on http://www.stpeters.sk.ca/crse/compare_the_share.doc.

9. Anxiety about the Multilateral Agreement on Investments, Ecological Agriculture Projects. 1997.

10. Rick Burroughs and Deborah Harper, “An Analysis of Profits within the Canadian Food Processing Sector,” Agriculture and Rural Working Paper Series Working Paper No. 59, November, 2002.

11. John M. Connor, “The Globalization of Corporate Crime: Food and Agricultural Cartels of the 1990’s. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Agricultural Law Association, Indianapolis, IN; October, 2002.

12. State of the Environment Report, PEI Government, June, 2003, p. 36.

13. This information can be found on: http://www.gov.pe.ca/af/agweb/numbers/stats/stats98/table43.php3.

14. State of the Environment Report, PEI Government, June, 2003, p. 10.

15. See MacRae, R. J. 1996. What does the research evidence say about the value of sustainable agriculture to communities? Sustainable Farming 6(3):5.

16. This news release can be found on http://www.agr.gc.ca/cb/news/2003/n30912be.html.

17. Sustainable agriculture is here understood as the production of high quality healthy food and other agricultural products using natural inputs and processes, with consideration for the entire environment, economy and social structure in such a way that the resource base of non-renewable and renewable resources is maintained and enhanced in the long-term. In their paper “Much More Difficult than we Think: The Very Problematic Character of Agriculture, Darrell McLaughlin and Michael Clow offer the following definition for Sustainability: “To be sustainable a human activity, as well as the means to carry it out, must be capable of being continued indefinitely. Ecological sustainability means an activity and how it is conducted can be continued indefinitely without continued environmental degradation.”

18. Announcement can be found on http://www.agr.gc.ca/cb/news/2003/n30814be.html.

19. There were only 150 certified organic producers in Sweden in 1985. By the Spring of 1996, just 11 years later, the figure had increased to 3,000. For more information on the transitional agricultural strategies of Sweden and other countries.